The Art of Writing Letters: Wartime Correspondence

Many people today would probably refer to writing letters as a dying art form, or an already dead art form. With the constant advancements in social media, email, internet, phone calls, video calls, and text messaging, putting effort into sitting down and writing a letter may seem fruitless. Why wait for the Postal Service to deliver a message you could type to someone and send momentarily?

Well, technological advancements today weren’t always around. There’s an important history behind the art of letter writing, and one of its most notable facets lies in what letters provided for people during times of war.

Notability during the late 19th and early 20th century, letters became an integral part of American life because letter writing provided an important form of communication between family and friends and was integral to the founding of our nation. Established in 1775, before our country was even founded, the U.S. Postal Service made its debut as the form of communication between Congress and colonial armies. In its early days, the Postal Service also delivered news and information to the public about political matters. The founding fathers used the postal service to conduct a campaign of sorts, by letting the public know about themselves and what they stood for through letters. As the first form of freedom of press, the U.S. Postal Service continued to grow in importance as time went on.

During the Civil War, soldiers often wrote to their loved ones as a source of keeping up the morale (USPS). In “The United States Postal Service: An American History,” the document reads, “A letter from home could be tucked into a pocket close to a soldier’s heart, to be read and re-read in moments of loneliness. Many soldiers carried letters in their pockets, to be forwarded to loved ones if they were killed in action” (18). Letters gave soldiers hope and comfort during war. They read and reread letters from loved ones and friends and wrote goodbye letters before going into battle so that if they died, their family would receive one last token of them to remember.

From wagons, horses, railroads, steamboats, cars, planes, and even Amtrak, the way letters were delivered and the time in which they were delivered evolved over the years. By the mid-1900s, Americans were receiving mail through weekly delivery. In the 20th century, the Postal Service evolved to not just deliver letters, but food, drugs, commodities, and large packages through Parcel Post, which began in the early 1900s (USPS, 38) and helped the economy immensely through merchandising. Airmail also became possible in the early 1900s (USPS, 40), and allowed for letter delivery to be quicker between the U.S. and foreign nations. Airmail also helped deliver letters quicker during the wars that would soon follow the first international delivery from New York to Montreal in 1929 (USPS, 43).

During World War 1, writing and receiving letters became imperative for soldiers. In the same way writing letters boosted morale during the Civil War, writing letters also boosted morale for soldiers during the first World War.

Letters during World War 1

During World War I, writing letters became the most popular form of communication between families, friends, and loved ones. Millions upon millions of letters were sent each month around the world — in Britain, 12 million letters were sent each week. Letters were mostly for morale, as soldiers felt hope and connected to their loved ones through writing letters, sharing stories, and reading about what their loved ones were doing back home. Letters were also used for other reasons, like relaying the daily news, sharing the details of training with other soldiers, and letting out the traumas and agitations of war. Lovers often sent letters to give hope to soldiers, but also for soldiers to give their lover waiting for them at home that they were okay.

Training

Historically, letters provide us with a deep insight into the trials and thoughts that soldiers dealt with during training for war. These letters also helped soldiers feel a camaraderie with their fellow soldiers, by sharing in their training experiences. The National Archives allows readers to view original letters written by soldiers during the war. A series of letters details life during training, as they write to their fellow soldiers.

Nicholas Boyce, for instance, writes a letter to his fellow soldier Lack, referencing a photo taken during training. Readers gain both a sense of what training was like for this soldier, but also get to feel his sense of fear towards going to war. After discussing the different types of physical exercises he goes through, such as “company drill mixed with route marches, physical drill, semaphore, knot tying and frog, long jumping etc” (National Archives), Boyce indicates to readers the emotional toll impending battle is having on him.

Boyce writes to Lack, “I enclose… postage for the photographs. If you are printing any more you might save me one as I am afraid I have spoilt mine, it got bent in my overcoat pocket on Saturday. Please remember me to all the office…” (National Archives). Boyce emphasizes his want for another copy of the picture of him and his fellow soldiers before going off to war. While not explicitly stated, this “lasting memento” has sentimental importance to Boyce, as it’s the last picture of him and his friends before being deployed to different locations, and possibly never seeing each other again. At this point in time, some of Boyce’s fellow soldiers had been sent into town, and others overseas, while he waited for his next orders. At the end he asks to be remembered, which shows how much this picture means not just for him to remember his peers, but for them to remember him, should anything happen during war.

Letters and photographs shared during war represented a chance to be remembered, and to remember others, while providing readers many years later with insights into the personal happenings of what soldiers thought about and did daily.

Trenches

Soldiers also wrote about their experiences in the trenches, and how awful and terrifying it was. From being in the trenches for weeks at a time, to standing in water nonstop for days, soldiers suffered day in and day out. These are just a few stories of what some soldiers went through while being in the trenches.

On June 19th, 1915, moving into the second year of WW1, soldier Richard Frederick Hull writes to his friend Gerald that “we were [in the trenches] for seven days…we had many casualties thirty five killed and one hundred and thirty eight wounded and I can assure you it was an experience I shall never forget.” Hull shares with his friend how the firing of weapons, working in the trenches for 7 days straight, and seeing fellow soldiers dying by the hundreds has worn him down. Seeing death and destruction nonstop takes a toll on the strongest of soldiers.

Just a month later, another soldier named William Albert Hastings writes to his friend Effie about what a “dirty job” it is to work in the trenches. He writes:

We are still in the trenches and have been in action twenty four days consecutively and I don’t know long we shall keep it up. Had a dirty time yesterday morning dodging damned great bombs the blighters were presenting to us without exaggeration they were eighteen inches to a two feet long and made a hole about ten feet deep and fifteen feet diameter at least we did not wait to see them burst. They can be seen descending through the air and then a scoot is made to get as far as possible round the corner, the iron and dirt seem to be falling for a minute afterwards, they are disturbing (Hastings).

From this excerpt of Hastings letter to Effie, readers and historians gain a lot of perspective on the images plaguing the soldiers every day. The image of dodging bombs day by day while being in what is essentially a line in the ground, with dirt serving as protection against a strong military arsenal, is horrifying. But Hastings allows himself to vent to his friend Effie about the horrors of war, perhaps allowing for a slight release of pent-up exhaustion and tension from emotional and physical turmoil.

Written a few months later on November 10th, 1915, from soldier Jonathan George Symons to his friend Bert, Symons depicts a scenario that caused a lot of soldiers to have “trench foot” which was first coined in 1915, from the horrific conditions of water and leakage in the dugouts. Symons writes:

The weather is simply awful, raining day after day and especially night after night…To tell you the truth, while writing this letter I am wet through to the skin and not a dry thing for a change. We have got our winter fur coats and gum boots, but the latter cause more curses than you can imagine, for instance last night I was sent off to select dugouts for our platoon, which is number 37. It was pitch dark, no light allowed and in a strange place, well honestly I fell over at least 20 times got smothered in mud from head to feet and on the top of that wet though for it rained in torrents (Symons).

Symons’ image of being soggy and wet, even while writing this letter to his friend, emphasizes how dangerous it was just to be in a trench under harsh weather conditions, in addition to gunfire and bombs targeting soldiers. He continues to say, “While in the trenches last week John and I were up to our knees in water and got our gum boots half full…. but one gets used to it.” Being in the trenches that long with their feet being constantly wet is why the term “trench foot” was coined in 1915, the year these letters were written. These letters serve to document the issues plaguing soldiers during this time, and why certain medically related terms, such as “trench foot” emerged.

Love Letters

While there were many letters that depicted the horrors and fears of war, many letters were exchanged between soldiers and their lovers. Writing love letters during wartime signified how important it was to soldiers to keep hope alive and to have something to look forward to, as they saw their brothers in arms dying every day, and suffered medical issues from the conditions of the terrain, and battle wounds.

The love story told in the letters Reg Roome wrote to Helen Jones during World War 1 attest to the importance of letter writing, especially for soldiers. Reg Roome writes to Helen about hope more than anything. On May 31st, 1915, he writes:

I kind of hope against hope that when I turn a corner it may be to run into you. Do I sound foolish? you ask. Isn’t that what I used to say in my letters of last year? Well, I’m there tonight, whether foolish or otherwise (Roome).

It is evident to the reader from the repeated use of the word “hope” in conjunction with the idea of Reg running into Helen, that his greatest hope is to see her again, as soon as possible. He wishes to have her near him and looks forward to being reunited. This theme of hope continues throughout all his letters, in which he dreams of libraries and sitting in one with Helen while reading Alice in Wonderland together.

In some ways, Reg also concludes that writing about love, about how Helen is his best friend and his lover, would be impossible to say in person but impossible to not write to her in a letter. On June 15th, 1915, Reg wrote, “I could not talk to you in the same way. You know it is hard to speak on such a subject. But you have made it easier for me and I trust that we both understand and I’m sure that we have been drawn quite a little closer together because of such confidences.” Writing letters has opened a new form of intimacy between the lovers, one in which Reg can communicate how deeply he loves Helen, while also sharing with her that she’s his best friend. While Reg feels comfortable calling another man or brother in arms his best friend, he finds himself unable to verbally say the same to Helen. He still finds it in himself to share this intimacy with her, however, in the letters he writes to her confessing his deepest feelings.

Reg also uses letters to tell his father-in-law, Dr. Jones, on April 20th, 1916, that he has a son-in-law. Due to the circumstances of war, Reg uses his letters as a way of asking form Dr. Jones’ daughter’s hand in marriage, despite marrying her without his consent beforehand. He writes, “Certainly, had we been at home this would not have happened for some time to come, but it is only because of the present conditions that I have taken the liberty. I trust that you will consent to her keeping it.” Already having been married during one of the brief moments of time Reg and Helen spent together during the war, he takes the opportunity to marry her. We can see how war has put an urgency on certain things that may have not happened had soldiers not been pressured under the possibility of death in war.

For Reg and Helen, their story had a happy ending. They lived happily married for over 50 years. The full correspondence between the lovers can be found here: ‘Remember that I love you’: A soldier’s letters to his sweetheart | CBC News

Unfortunately, not all love stories ended happily. For Private William Martin and his fiancée Emily Chitticks, love letters turned into a sad ending for Emily. Emily wrote her lover a very heartfelt letter, only to learn later that he had died in battle before she even sent her letter to him. She begins this love letter by telling her future husband that she has no news to tell him, but she’s awaiting news from him with hope and excitement. She tells her lover not to worry about her “because I know God can take care of you wherever you are and if it’s his will darling he will so are you to come back to me, that’s how I feel about it dear, if we only put our trust in Him. I am sure he will” (Chitticks). She puts her faith in God that they will be together again, and that William will come back to her safely and write to her as soon as possible. She continues to ask him questions and tell him about the family in the rest of the letter, hoping with everything inside of her for a reply.

Emily post-scripts the letter: “Cheer up darling, and don’t worry about me. I am quite alright, only anxious to get your letters. There is good news in the papers. Love from Mum and Dad” (Chitticks). Despite a lull in his letters to her, she is “anxious” to hear back from him and references the “good news” in the papers, showing how hopeful she is about his condition in the war, and that everything will be okay for them. To write about hope and a future for them, only to hear the news that he had been killed in action, shows the devastations of war, the way it squandered hope, and tore families apart.

Despite their not-so-happy ending, these words signify the hope that letters allowed people to have during these times.

Childhood Horrors

Some letters sent during war were quite sweet, but others were absolutely horrifying when you realize the terrific images children must have seen on a daily basis.

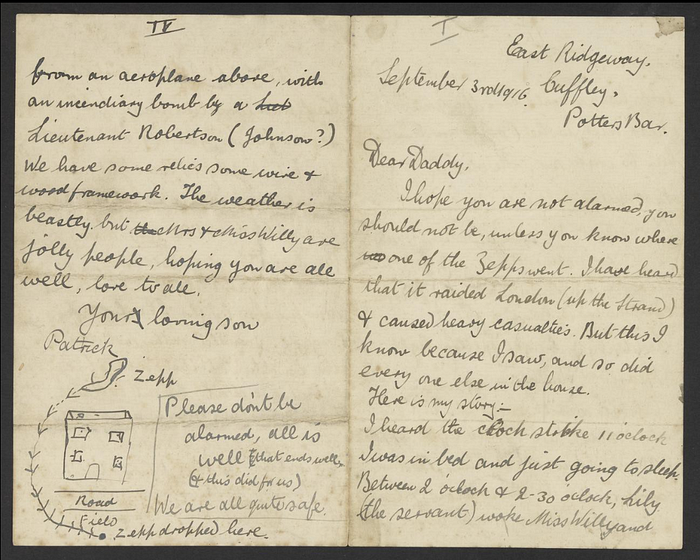

Patrick Blundstone, a young schoolboy, wrote to his father in September of 1916 to share the images he had seen earlier that day of the destruction of a Zeppelin airship. Beginning the letter with “Dear Daddy,” the tone of this letter changes quickly, as Patrick begins to recount the events that unfolded before his young eyes that day. Awakened by the sound of gunshots, his family woke up during the night in fear of what was happening outside their home. Peering outside the window, Patrick sees a Zeppelin crashing through the sky and into the ground. He shares:

I would rather not describe the condition of the crew, of course they were dead — burnt to death. They were roasted, there is absolutely no other word for it. They were brown, like the outside of Roast Beef. One had his legs off at the knees, and you could see the joint! (Blundstone)

Patrick speaks casually, and quite excitedly about this destruction of the Zeppelin, as well as the crew inside of it. Perhaps Patrick is not yet affected by the images he sees, as he describes these people akin to “Roast Beef” and uses many exclamation points throughout this letter to show his surprise and excitement at what he saw. The return letter from his father was not included in this collection, but you — the reader — can imagine what it must have been like for his father to read a letter about his little boy seeing dismembered body parts of men dead from battle.

All About Letters, Letters, Letters

Letter writing is important. It’s important historically, it’s important to those individuals who used writing letters to facilitate hope, love, and camaraderie, and it’s important to us today in understanding what it was like for people to live in the past. The Postal Service and the opportunity for international mail service was, and still is, imperative in keeping communication alive between distance parties.

Writing letters isn’t just important because of war. There are certain historical figures that we would not know about today if we did not have access to their letters. Check back in soon to read my next blog that features several prominent figures that we know about because of letters they wrote to others!